The Crimean Budget. Small Business. Salaries and Pensions / 2014-2021

The Monitoring Group of BlackSeaNews

and the Black Sea Institute of Strategic Studies

presents an updated series of articles

«The Socio-Economic Situation in Occupied Crimea in 2014 – 2021»

Back in the USSR. The Reverse Restructuring of the Crimean Economy / 2014-2021

The "Trophy Economy". Militarization as a Factor of Industrial Growth / 2014-2021

The "Trophy Economy". The Development of the Stolen Ukrainian Black Sea Shelf / 2014-2021

The Crimean "Trophy Economy": The Sale of Ukrainian Property. An Updated Review for 2014 – 2021

The Occupied Crimean Tourism / 2014-2021

Occupied Crimea. Exports and Imports / 2014-2021

The Banking System of Crimea: What is Really Happening on the Occupied Peninsula (Updated)

Investment. What the "Crimean" Federal Target Programme Finances / 2014-2021

«Migration weapons»: the replacement of the Crimean population with Russian

Water in Occupied Crimea / 2014-2021

The Crimean Budget. Small Business. Salaries and Pensions / 2014-2021

Crimean Budget

After 2015, it became clear that the regime of international sanctions and the blockade of the occupied peninsula by mainland Ukraine made not only the economic development but also financial self-sufficiency of Crimea and Sevastopol impossible. Since then, the analysis of the budgets of Sevastopol and "the Republic of Crimea" has lost its economic sense.

The basis and, at the same time, the main intrigue of the annual budgeting in Crimea are the same – the size of the subsidies from the Russian Federation.

Due to the sanctions, Russia has had to use the only possible "economic model" for occupied Crimea, the main features of which are as follows:

-

"the island of Crimea" is isolated from the civilized world and connected only with the Russian Federation by the bridge across the Kerch Strait, the underwater gas pipeline and power cable, and by air;

-

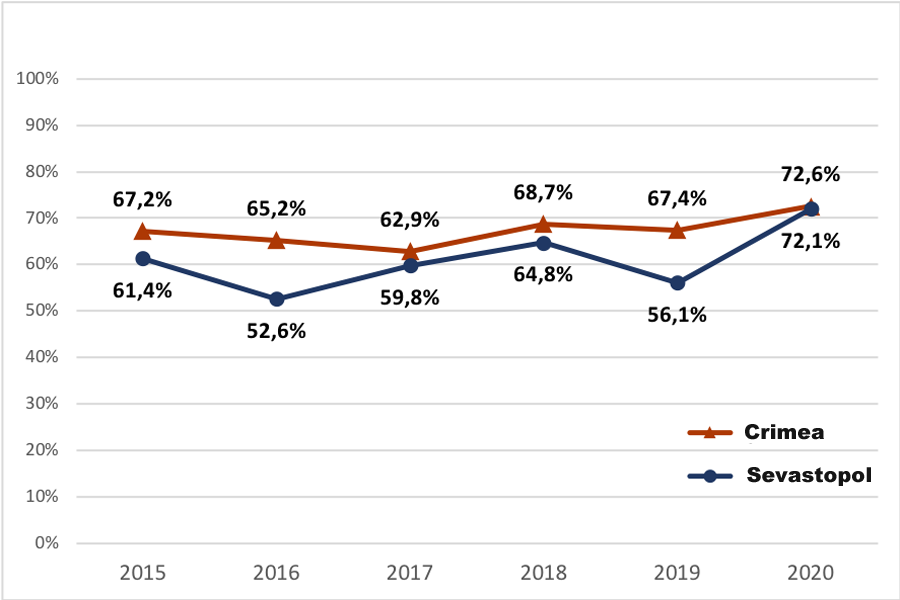

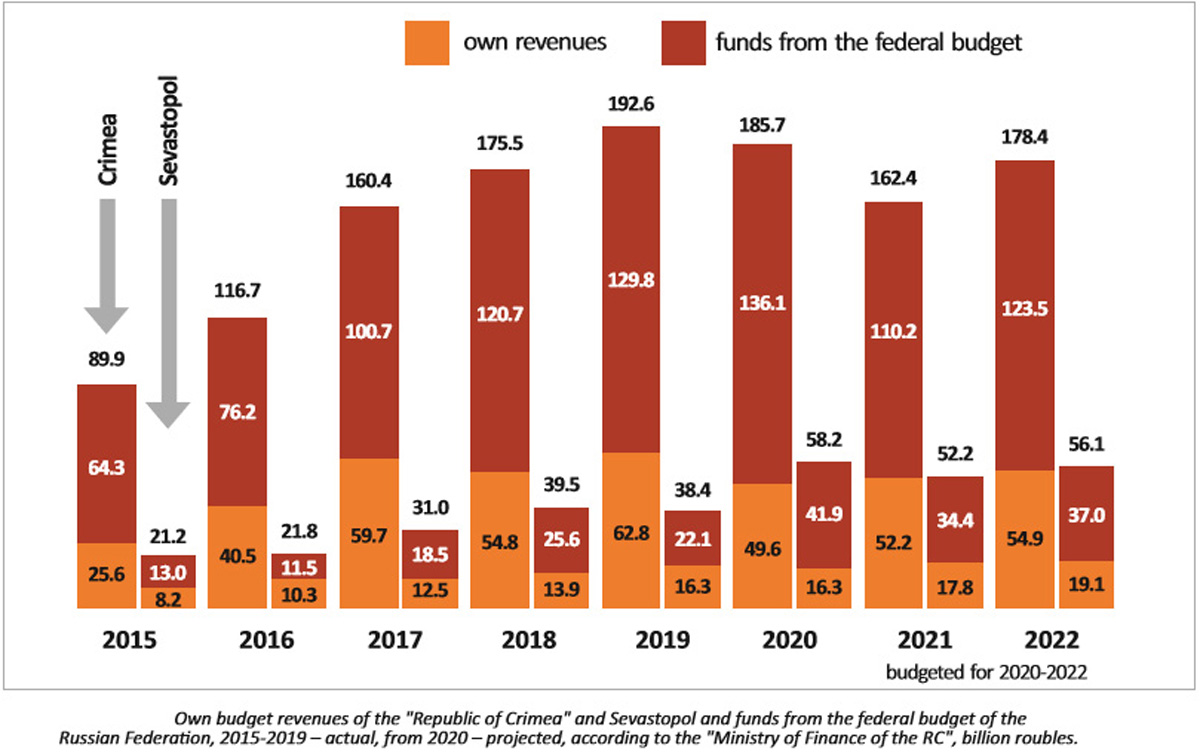

almost 70% of the "island’s" expenses are covered by the subsidies from the Russian Federation’s budget; some income comes from the sale of "trophy" Ukrainian property, the buyers of which are Russian companies and individuals under international sanctions;

-

the civilian, military, industrial, logistical, and service infrastructure of the "island" has been created mainly on the basis of "trophy" Ukrainian property; its development and maintenance are funded by the Russian government – be it budget financing or the funds of state-owned and quasi-private companies. This work is carried out mainly by Russian companies put on sanctions lists.

In terms of the level of subsidies, occupied Crimea is in the same group as the most heavily subsidised regions of the Russian Federation: the republics of the North Caucasus (Chechnya, Ingushetia, Karachay-Cherkessia, Dagestan) and such remote areas as Altai, Tyva, and Chukotka.

A certain increase in revenues in 2019 was artificial as registered offices of some companies involved in the construction of the bridge across the Kerch Strait were moved to Crimea in order to pay taxes to the Crimean budget. Due to the completion of the megaprojects, such revenues are no longer projected.

The slightly lower level of Sevastopol’s dependence on subsidies is explained only by the fact that, as a result of the militarization during the occupation, many members of the Russian armed forces and their families, who have quite high incomes and pay taxes to the local budget, have moved to the city. According to the authors' estimates, during the occupation, the population of Sevastopol has increased by at least 100%.

At year-end 2019, the occupied Ukrainian regions were among the ten most heavily subsidised regions of the Russian Federation: (74) the Republic of North Ossetia – 56.4%; (75) Sevastopol – 57.6%; (76) Kaliningrad Oblast – 57.6%; (77) the Kabardino-Balkarian Republic – 59.0%; (78) Chukotka Autonomous Okrug – 62.7%; (79) "the Republic of Crimea" – 67.4%; (80) the Republic of Dagestan – 67.5%; (81) the Altai Republic – 70.3%; (82) the Karachay-Cherkess Republic – 71.5%; (83) the Tyva Republic – 75.9%; (84) the Chechen Republic – 80.6%; (85) the Republic of Ingushetia – 88.2%.

Small and Medium-Sized Business

Since 2014, the Crimean small and medium-sized business has been in decline and the process of its replacement with the entrepreneurs from the Russian Federation has been taking place. Crimea has also seen the expansion of the Russian business into the profitable segments of the peninsula’s economy (see The Trophy Economy. The Commercial Exploitation of Marine Biological Resources section). All this in the absence of reliable statistics makes traditional statistical analysis imp¬ossible.

Experienced Crimean entrepreneurs state that small business in Crimea has faced a significant increase in the number of reports required, a huge number of auditors, and a harsh system of heavy fines, even for the smallest violations.

After the occupation, the category of tourists arriving in Crimea from Russia has changed from high-income visitors to low-income ones, which, in turn, has led to a drastic reduction in the number of small businesses in the tourism industry. Before the occupation, about 21% of the adult population of Crimea, or over 350 thousand people, including 9% in rural areas, 16% in industrial areas, and 32% in the resort regions, were engaged in providing tourist services as seasonal work. Nowadays this main industry of the Crimean small business has no prospects.

According to forecasts made by the authors of this report, the decline of small business in Crimea will continue.

The experience of the years of the occupation shows that entrepreneurial activity, critical thinking, and independent decision-making are antagonistic to the social model of contemporary Russia.

Salaries and Pensions

One of the main slogans used before the Crimean "referendum" on 18 March 2014 was the argument about significantly higher levels of salary, pensions, and social welfare spending in the Russian Federation.

The Crimean residents imagined that the consumer spending power of an average Russian citizen is close to that in Moscow, St. Petersburg, and other big and successful Russian cities, as well as that of the Russian Black Sea Fleet servicemen in Sevastopol, who had received special foreign service remuneration.

During the initial stage of the occupation, the occupying power actually fulfilled those promises.

In March 2014, salaries in state organizations and institutions started to be paid in Russian roubles. Whereas the hryvnia – rouble exchange ratio for commercial organizations was 3.0, which corresponded to the market value at that time, for public sector workers and retirees, this ratio was increased to 3.8. That is, these categories of the population received a "treason bonus".

As in 2014 Ukrainian foodstuffs, generally of much better quality and less expensive than Russian ones, still dominated Crimean store shelves, in the first year of the occupation, the retirees, officials, teachers, and doctors could claim an increase in their spending power. However, since 2015, the real Russian remuneration and pension systems have been applied on the occupied peninsula.

In the meantime, Ukrainian goods in Crimea were gradually replaced with more expensive Russian equivalents. At the end of 2015, all supplies from mainland Ukraine were terminated.

In 2016, it became clear that Russian salaries and pensions proved to be far lower than the advertised 2014 model. Combined with higher Russian prices for consumer goods, the devaluation of the rouble as a result of aggression against Ukraine, sanctions, and the falling oil price, that led to the complete disappearance of the "2014 effect".

The reduction in the number of jobs available to the Crimeans caused by the migration from Russia of up to 1 million people has put an additional strain on the income level of the local population (See The Replacement of the Population of Crimea section). For example, the majority of spouses of the Russian military and security services personnel transferred to Crimea are educators.

18% of Crimean employees receive a salary of up to 15 thousand roubles a month (about $200); 2.3% earn more than 100 thousand roubles a month ($1,300), while most employees have an income of 17 to 37 thousand roubles a month ($220 - $480).

In 2020, Crimea was included in the list of the 10 "Russian regions" where people have the lowest income levels. One of the leading rating agencies of the Russian Federation ranked Crimea 76th out of 85 regions in terms of the income level of the population. That means that only the population of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast, the Mari El Republic, Kurgan Oblast, the Karachay-Cherkess Republic, Ingushetia, Kalmykia, Altai, and the Tyva Republic has a lower income level than people in Crimea.

In 2020, Crimea ranked 78th out of 85 in the ranking of the "Russian regions" in terms of consumer demand. From January to July 2020, the consumer demand in Crimea decreased by 11.3% year on year.

In September 2020, experts of the Accounts Chamber of the Russian Federation concluded that the Federal Target Programme "The Socio-Economic Development of the Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol" would not bring the standard of living of the peninsula’s population to the Russian national average and eliminate disparities in regional development, as the projected values of certain indicators were insufficient. Thus, according to the agency, by 2022, the average salary in Crimea and Sevastopol should reach 38,300 roubles a month. However, in the Russian Federation, that indicator was 43,400 roubles at year-end 2018.

In 2020, Crimea and Sevastopol ranked in the bottom 5 "Russian regions" for mortgage affordability. Crimea ranked 82nd out of 85, Sevastopol – 81st. Fewer mortgages were taken out only in Dagestan, Chechnya, and Ingushetia.

Overall, occupied Crimea has turned into an ordinary "Russian backwater" with the low standard of living and quality of life. No significant changes are expected.

* * *

This article has been published with the support of ZMINA

Human Rights Centre.

The content of the article is the sole responsibility of the authors.

More on the topic

- 21.08.2023 Peculiarities of the 2023 Crimean Holiday Season — a «Tourism» in Camouflage

- 06.08.2023 Crimea During the Great War. Part 2. Extreme Tourism or «New Types of Tourism» and Tourist Numbers (2)

- 21.07.2023 Crimean Titan: Under a Russian Holding or a Ukrainian Tank?

- 12.06.2023 Crimea during the Great War. The situation in the occupied Crimea in 2022-2023. Military Context (1)

- 23.11.2021 Occupied Crimea. Exports and Imports / 2014-2021

- 23.11.2021 Water in Occupied Crimea / 2014-2021

- 23.11.2021 The "Trophy Economy". The Commercial Exploitation of Marine Biological Resources in the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov / 2014–2021

- 21.11.2021 The "Trophy Economy". Militarization as a Factor of Industrial Growth / 2014-2021

- 21.11.2021 Back in the USSR. The Reverse Restructuring of the Crimean Economy / 2014-2021

- 20.11.2021 The "Trophy Economy". The Development of the Stolen Ukrainian Black Sea Shelf / 2014-2021

- 20.11.2021 The Occupied Crimean Tourism / 2014-2021

- 20.11.2021 Investment. What the "Crimean" Federal Target Programme Finances / 2014-2021