How the Sanctions Work. The Defense Industry of the Occupied Crimea

by Tetyana Guchakova,

the Monitoring Group expert, Chair of the Board, Institute for Black Sea Strategic Studies

It won’t come as news to anyone that the main purpose of the Russian occupation of Crimea was not so much the proverbial «gathering of the Russian lands,» but first and foremost, the creation of a huge military base.

The occupied Crimea has become a base for troops and armaments, an important logistical point in the Russian military operations in Syria, and a convenient locale for much of the military-industrial complex formed with the captured Ukrainian enterprises.

The composition of the military-industrial complex of the Crimea

The military-industrial complex of the occupied peninsula de facto consists of:

- large enterprises that were seized by the Russian Federation in the first months – mostly in the first weeks – of the occupation and

- private industrial enterprises, subsequently re-registered under the Russian law.

On April 4, 2014, Russian Defense Minister Serhiy Shoigu announced his intention to load the industry of the occupied peninsula with a state defense order, emphasizing the importance of «effective use of the production and technological potential of the Crimean defense industry.»

As early as mid-April 2014, the RF Ministry of Defense has already formed a list of 23 Crimean companies of interest to the agency.

At the beginning of 2014, the Ukroboronprom concern included 13 Crimean enterprises, namely:

Feodosiia Shipyard More State Enterprise

Feodosiiskyi Optychnyi Zavod (Feodosiia Optical Plant)

PAT Zavod Fiolent (Fiolent Plant), Simferopol

State Enterprise Konstruktorsko-Tekhnolohichne Biuro Sudokompozyt (Sudokompozyt Design and Technology Bureau), Feodosiia

State Enterprise Naukovo-Doslidnyi Instytut Aeropruzhnykh System (Research Institute of Aeroelastic Systems), Feodosiia

State Enterprise Yevpatoriiskyi Aviatsiinyi Remontnyi Zavod (Yevpatoriia Aviation Repair Plant)

State Enterprise Sevastopolske Aviatsiine Pidpryiemstvo (Sevastopol Aircraft Enterprise)

State Enterprise Skloplastyk, Feodosiia

State Enterprise Feodosiia Ship and Mechanical Plant of the Ministry of Defence of Ukraine

State Enterprise Central Design Bureau Chornomorets, Sevastopol

State Enterprise Spetsialna Vyrobnycho-Tekhnichna Baza Polumia (Special Production and Technical Base Polumia), Sevastopol

State Enterprise Research Centre Vertolit, Feodosiia

State Enterprise Konstruktorske Biuro Radiozviazku (Radiocommunications Design Bureau), Sevastopol.

Besides Ukroboronprom, several other large enterprises best fitted for fulfilling defense orders, such as Zaliv Shipyard, the Sevastopol Marine Plant PJSC, and the Omega Testing Center have been seized as well.

In addition, in anticipation of large defense orders, several private enterprises also have been quickly re-registered under Russian law.

The following are just some of the enterprises in Sevastopol that have already fulfilled Russian state defense orders or cooperated with Russian military enterprises:

| Name before the occupation | Name after the registration under Russia law |

|---|---|

| PJSC Scientific and Technical Enterprise Impuls-2 | JSC NTC Impuls-2 |

| Uranis, LLC |

Uranis, LLC Uranis-Radiosistemy, OJSC |

| Pivdennyi Sevastopol Shipyard, LLC | Yuzhnyi Sevastopol Shipyard, LLC |

| Persei+, LLC | Persei Shipyard, LLC |

| Sorius Shipyard, LLC | Sorius Shipyard, LLC |

| Private enterprise Sorius | Sorius, LLC |

| Nautilus-Sev, LLC | Nautilus-Sev, LLC |

| Tekhflot, LLC | Tekhflot, LLC |

| Private enterprise Shipyard Fregat | Shipyard Fregat, LLC |

| Empirei і Cо, LLC | Empirei і Cо, LLC |

| Sevastopolske pidpryiemstvo Era, LLC | Sevastopolskoye predpriyatiye Era, LLC |

| Zavod sudnovoi svitlotekhnyky Mayak, LLC | Zavod sudnovoi svitlotekhnyky Mayak, LLC |

| Zavod Molot, LTD | Zavod Molot-Mekhanika, LLC |

| Sevmormash-2М, LLC | Sevmormash-2М, LLC |

| PJSC TCB Korall | JSC TCB Korall |

| Yugprombud, LLC | Sevastopol Agregatnyi Zavod, LLC |

| Private enterprise Vyrobnychno Komertsiina Firma Valm | Shipyard Valm-Rus, LLC |

.jpg)

Over time, the booty Crimean have gone through intricate metamorphoses enterprises, changing their corporate and legal form and ownership type and having their property transferred to other legal entities. Some of the changes involve an attempt to "optimize" the company structure in view of international sanctions and other legal challenges.

For example, Feodosia's Skloplastyk became part of the More Shipyard, which has already been transformed into a joint-stock company and included in the plan for the "privatization of federal property" for 2020-2022. "Privatization" should become a legal form of transfer of the seized plant of the Russian State Corporation "Rostech", which was initiated by Putin's decree in May 2018.

Sevastopol CCB "Chernomorets" ceased to exist after joining the "Sevmorzavod", becoming a design center. Sevmorzavod itself has been a Branch of the Sevastopol Marine Plant of the Zirochka Ship Repair Center JSC since the beginning of 2015.

And the founders of Uranis LLC, re-registering the company under Russian law, divided it into two legal entities: one (OJSC Uranis-Radiosystems) - to work with Russian defense orders, the other (Uranis LLC) - for foreign economic activity.

Russian defense companies have been setting up branches and subsidiaries in the occupied territories.

For example, in January 2015, the Leningrad shipyard Pella registered Kaffa-Port LLC in Feodosia to work at the More Shipyard leased by Pella. Kaffa-Port has already completed its task and is in the process of liquidation.

Creating a comprehensive list of Crimean enterprises that work with defense orders is no easy chore. But according to the official information, the Russian Federation considers that there are 16 defense industry enterprises in the occupied peninsula. Of these, ten are shipbuilding facilities, three — aviation, two — conventional arms and one — electronics.

As of 2017, the RF registry of the defense industry enterprises includes eight in the "Republic of Crimea" and four in Sevastopol.

Periodically, manufacturers of civilian products also make attempts to work for the Russian «defense,» but not everyone succeeds, considering that sometimes, even the Crimean producers already included in the registry fail to do so.

The problem is that Russian defense industry is huge and competition for the state defense orders is harsh, while international sanctions complicate the situation further.

From May 2015 to August 2017, the RF Ministry of Industry and Trade practiced the official appointment of the so-called "curators" of the Crimean plants from among the relevant Russian manufacturers who were to share state defense orders with the Crimean plants and modernize them.

The official «curatorship» ceased in August 2017 after the new list of the "Crimean" US sanctions was adopted.

In October 2019, the «head of the Crimea» Sergei Aksyonov said that «as of September 1, the total volume of contracts fulfilled at the Crimean defense enterprises amounted to more than 21 billion rubles, including 17 billion – from state defense order. The plant load factor averaged 40%.»

Oleg Zachinyaev, director of the Feodosiya shipyard More, when commenting on the impact of sanctions on the company's operation, emphasized that «ships and vessels under the Crimea development federal target program are built not by the Crimean, but by mainland companies that have won tenders.» He added that «we lose in public procurement due to logistics and sanctions that hamper the options of purchasing all sorts of equipment directly. It’s no secret that more than 50% of components and equipment for the ship and vessel construction are imported. So, we are now forced to procure them via various schemes, thus, losing to our partners who purchase those directly. Besides, noone wants to participate in our tenders in the fear of falling under the sanctions for cooperating with the Crimean enterprises.»

Sanctions with the greatest impact on the military industry

Most of the Crimean enterprises classified as those belonging to the military-industrial complex are on the sanctions lists by either Ukraine or both the US and Ukraine, while the Zaliv shipyard is also on the EU lists.

There is also a general investment ban and a US/EU ban on the export or import of goods, technologies and services to/from the occupied Crimean peninsula.

However, given the large-scale industrial cooperation in this area (see below), sanctions against Crimean legal entities alone are not Russia’s biggest irritant.

A considerable number of large Russian defense enterprises cooperates with Crimean enterprises and sanctions against the former are much more painful. Many of those companies are already on the US Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) lists: namely, in the Specially Designated Nationals List (SDN) and Sectoral Sanctions Identifications List (SSI).

Depending on the list type, those entities/persons fall under a variety of restrictive measures that range from the blocking of assets to prohibition of certain operation types, with the sanctions also extending to shares of such entities/persons owned by other entities.persons when those exceed 50 percent.

As can be seen from the practical consequences, Russia’s continuous effort to find the circumvention schemes and state-level decisions conceal information, export restrictions on the supply of industrical goods and technologies industry have proven to be the most effective ones.

The first restrictive measures on the export of defense products to Russia were introduced by the United States on March 1, 2014. The Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS, an agency of the US Department of Commerce) has suspended licensing of exports and re-exports of dual-use goods to Russia. In March, the licensing of the defense goods exports was suspended.

In April 2014, the US imposed additional restrictive measures on the export of defense products to Russia, while the previously issued export licenses for the supply of high-tech goods in Russia were revoked. In addition, the BIS imposed additional export restrictions on 13 Russian companies that were already on the OFAC sanctions list.

In the time since the beginning of the Russian aggression against Ukraine, the BIS has repeatedly expanded the export restrictions Entity List.

By the end of 2020, the list already included 289 Russian legal entities, 160 of which are also on the OFAC SDN or SSI lists, and 129 legal entities that are not on the OFAC lists.

We have updated the database of legal entities that are under Ukrainian, US and EU sanctions in connection with the aggression against Ukraine, having added information on the inclusion of legal entities in the Entity List.

The inclusion in the Entity List means the obligation to obtain a license for export, re-export and/or transfer within the country of the goods:

- from the USA

- manufactured in the United States

- manufactured overseas with certain US components or technologies.

Such companies need to obtain an export license for all goods, including those that are not included in the Trade Checklist and normally do not require a license.

Under the current rules, the BIS considers such license applications with a presumption of denial.

In 2020, the US continues to tighten the regime of technological sanctions against Russia: there are more and more general restrictions on exports to Russia, including even those goods intended for civilian use only that previously did not require licensing, such as bearings, semiconductors, computers, etc. On October 29, 2020, the presumption of denial in regard to export licenses for the supply of all goods that can be used for military purposes, came into force.

On July 31, 2014, the EU introduced its own restrictions on exports to Russia.

Along with oil industry technologies, arms and military equipment and dual-use goods and technologies fell under restrictions.

It is prohibited to sell, supply, transfer or export, directly or indirectly, dual-use goods and technologies, regardless of whether or not they have the EU origin, to any natural or legal entity, resident of Russia or for use in the RF, if those items are intended or may be intended, in whole or in part, for military use or for the military end user.

If the end user is the Russian military, any dual-use goods and technologies purchased by them are considered intended for military use.

When considering applications for permits, the competent authorities shall not authorize the export to natural or legal persons, entities or bodies in Russia or for use in the RF if they have reasonable grounds to believe that the end-user may be related to military or that the goods may have military use.

In August 2014, by Presidential decrees Ukraine officially imposed restrictions on the export of military and dual-use goods to Russia. Intergovernmental agreements with the Russian Federation on military-technical cooperation and on production and scientific-technical cooperation of defense industry enterprises were officially terminated by the Cabinet resolutions in 2015.

How Russia is trying to avoid sanctions

Industrial technological processes in Crimea somewhat differ from other sectors there requiring cooperation of numerous different manufacturers, while current work load of Crimean enterprises requires their integration into large Russian technological chains.

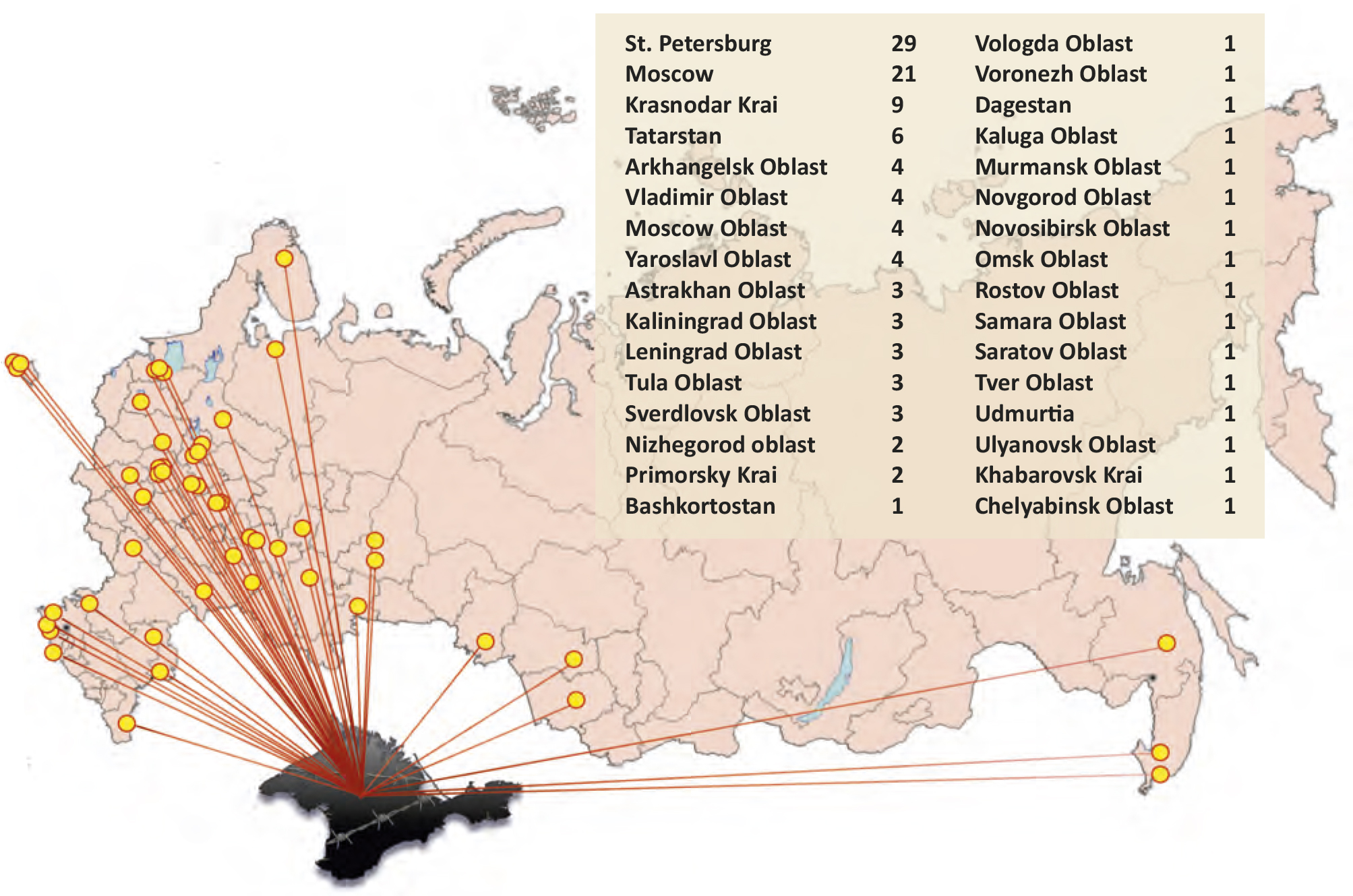

As early as early 2019, the Monitoring Group of the Institute of Black Sea Strategic Studies identified at least 150 companies from all regions of the Russian Federation that cooperate with Crimean enterprises involved in fulfilling defense orders.

Given the technological specifics, schemes to circumvent sanctions in the military industry is not just a matter of each individual enterprise, but rather, Russia’s state policy.

The key element of this policy is secrecy.

Since 2015, Russia has taken a number of steps to shut down leakage of information on production links with toxic enterprises, namely:

- In September 2015, the registry of the RF defense industry enterprises stopped being public (RF Government Resolution #944 of September 7, 2015).

- Procurement rules for companies in the industry have also changed:

- In November 2017, even before the relevant amendments to the legislation, the lead industry enterprises — more Russian than Crimean — obtained government directive # 8582p-P13 that ordered transfer of all company procurements to the classified electronic trading platform Automated System of Trade for the State Defense Order (AST-DOZ) established in February 2017 as a joint project of Sberbank-AST and Rostech Corporation, as well as to conceal information on the name and location of the procurement parties in all protocols and minutes.

- In April 2020, a new federal law dropped the obligation for executors of state defense orders to enter information on procurement in the unified public procurement information system. Prior to that, a procurement plan inclusion was required.

From the explanatory note to the draft law:

«Given the effect of international sanctions on defense companies, the disclosure of procurement information actually means the disclosure of information about the interaction of suppliers with a person included in the sanctions lists, which causes negative consequences for both the suppliers — discredits them and facilitates their inclusion in the sanctions lists and revocation of their export licenses — and the defense industry enterprises, in particular, impossibility to purchase products of the sanctioned origin, non-receipt of products under the concluded agreements and refusal of suppliers to interact with the defense industry enterprises. These consequences occur regardless of the type of products offered and stem from the international sanctions against defense companies.»

3. Public information about the sector enterprises has been shut down:

- in November 2017, also before the adoption of the respective amendments to the legislation, on government directive # 8583p-P13, defense companies got the right not to disclose information that they had previously had to in accordance with the laws «On Joint Stock Companies,» «On Securities Market,» «On Financial Leasing,» «On State Registration of Legal Entities and Individual Entrepreneurs,» «On Credit Histories,» « On Consolidated Financial Statements,» «On Accounting» and «On State Defense Order»

- in the future, the relevant laws and regulations were gradually adopted, for example, the RF Government Resolution #729 of 06.06.2019 stipulated that access to some of the information in the unified state registry of legal entities should be closed if the legal entity:

▸ is under international sanctions

▸ is a bank that serves the state defense order

▸ is located in Crimea or Sevastopol;

▸ has branches or offices in Crimea or Sevastopol.

How the sanctions work

Initially, in 2014-2015, when reacting to sanctions, the Russian Federation pushed a thesis that sanctions were good for the Russian economy because they stimulated domestic import substitution.

However, by now, that thesis has long been forgotten, as "import substitution" in the fields of instrumentation, mechanical engineering, military industry and equipment for oil and gas fields has failed.

Military ship and aircraft construction illustrates it best.

Shipbuilding

For modern Russian shipbuilding, including military one, unimpeded access to Western technologies, components and equipment is a necessary condition that allows timely fulfillment of the navy modernization tasks.

Conversely, the lack of such access leads to multiple delays with some warship construction projects now shutting down completely.

From the RF shipbuilding industry development strategy till 2035 approved in 2019:

«Currently, the foreign components share in the cost structure of ship equpment ranges from 40 to 85 percent for the civilian sector, and 50 to 60 percent for military shipbuilding.

The main reason is the low competitiveness of a wide range of domestic ship equipment due to low quality and high cost of the components, lack of warranty repair and maintenance, non-compliance with modern environmental requirements and lack of domestic production of a number of ship equpment positions.

[…] the industry is heavily dependent on foreign supplies of equipment and other countries sanction policies, which threatens the possibility of building certain types of ships and marine equipment in the Russian Federation. The high share of foreign products in ship equipment and fluctuations in exchange rates create risks of rising costs and disruption of shipbuilding and marine equipment building. The de-facto absence of the domestic electronic component base, break-up of collaboration patters, flawed system of works coordination and difficulty of the prompt replacement of a component with an analogue also considerably affect the production processes in the shipbuilding industry.»

At present, the main problem of Russian military shipbuilding is its inability to obtain Ukrainian and German engines, the main power modes.

As an example, let’s take project 11356 missile frigates that were supposed to join the RF Black Sea Fleet.

The project provided for the installation of engines by the Ukrainian State Enterprise «Research and Production Complex of Gas Turbine Construction Zorya-Mashproekt.» In 2011, when Russia announced the start of large-scale rearmament of its army and navy, the construction of six such frigates was planned.

Three of the ships – Admiral Grigorovich, Admiral Essen and Admiral Makarov – were completed and handed over to the BSF in 2016-2017.

However, there was’t enoughtime to install Ukrainian engines on the rest before the sanctions were imposed. The Russian government set a task to replace the import of Ukrainian engines at Russian enterprises, but it failed.

As a result, it was decided that two frigate hulls, previously intended for the Russian BSF – Admiral Butakov and Admiral Istomin – will be completed at the Kaliningrad’s Yantar plant and sold to India without the engines, while India intends to purchase them from Ukraine.

The last one, Admiral Kornilov, will be completed in India at the Goa Shipyard Limited.

Most likely, this means the end of the project 11356 frigate production.

The project 22350 frigates at St. Petersburg’s Northern Shipyard encountered a similar problem.

Back in 2010-2011, the Russian Defense Ministry signed a contract with the Northern Shipyard for the construction of six 22350 project ships. All of them had to be built and handed over to the Navy by 2018.

The plans were thwarted by the lack of supply of Zorya-Mashproekt power plants. Only at the end of November 2020, the United Engine Corporation (part of Rostech) announced the supply of the first Russian diesel turbine unit for the project vessels.

On July 20, 2020, when Putin visited the occupied Kerch, the last two project 22350 frigates that were to be handed over to the Navy by 2018, were laid at the Northern Shipyard during the «videoconference of the ceremony of mass navy ship laying».

Meanwhile, construction of a series of project 21631 small rocket ships (corvettes), faced a problem due to the lack of engines from Germany’s MTU Friedrichshafen GmbH.

The series that is being built by the Gorky Zelenodolsk plant, is supposed to consist of 12 ships: three for the Caspian flotilla, six for the Black Sea Fleet and three for the Baltic Fleet. But the plant managed to install German engines on five ships only.

After the German company refused to supply additional engines for the ship series, the task of import substitution was laid upon the Kolomenskoye plant and St. Petersburg’s Zvezda plant.

After the attempt failed, the Russian Navy command decided to put Chinese engines on the remaining ships of the series, namely the Henan diesel engines licensed by the German Deutz-MWM that had left the high-speed marine diesel market of — a 1980s design model. However, according to the Russian experts, «the Chinese product does not fully meet the Navy operating demands.»

To date, eight ships of project 21631 — three of them with the Chinese engines — have been turned over to the Nacy, while the rest remain under construction.

It looks like Russia will have to give up further construction of the project 21631 corvettes.

The list of Russia's naval shipbuilding troubles due to the international sanctions can be continued.

The phrase «shift of the terms to the right» has practically become a mem in both the Russian media and the officials' reports pertaining to shipbuilding.

Naturally, sanctions also have a direct impact on Russia's outcomes in creating the defense industry complex in Crimea.

For example, the reason why the Leningrad Pella Shipyard stopped construction of the project 22800 Karakurt missile corvettes for the Russian BSF at the Feodosiya More Plant and suddenly began to redeploy the unfinished ship hulls to the Leningrad region is certainly the threat of sanctions.

The situation with Pella's operation in the occupied Crimea has received considerable publicity. Meanwhile, since March 10, 2014, the Pella plant through its subsidiary Pella Sietas GmbH: Neuen-felder Fardeich 88, 21129 Hamburg, www.pellasietas.com has been the owner of the German J. J. Sietas Shipyard.

Pella left the More plant in the fall of 2019, a year before the lease end.

All three unfinished ships, two of which — IRC Kozelsk and Okhotsk - were scheduled to be turned over to the Navy in 2019, were towed by river to the Pella plant in the Leningrad region.

At the same time, two ships — IRC Okhotsk and Vikhr — spent the winter of 2019/20 in the port of Rostov-on-Don.

Aircraft building

Developer and manufacturer of aviation equipment PJSC Beriev Taganrog Aviation Scientific and Technical Complex (TANTK), part of the United Aircraft Corporation (UAC), that since the beginning of the Crimean occupation, has been cooperating with the Yevpatoria Aircraft Repair Plant, has experienced problems with the production of a new Be-200 amphibious aircraft.

In the spring of 2019, Russian media reported that the Ukrainian D-436TP engines manufactured by Motor Sich will be replaced by the Russian PD-10. But there was one problem: the Russian engine did not yet exist — it had yet to be developed. Only in October 2020 it was reported that the new engine, PD-8, may be ready in 2022, after which an attempt to install it on the aircraft may be made the following year.

The A-100 Premier new generation long-range radar detection and control aircraft, developed mainly by the Vega concern — part of the Roselectronics holding — was expected to be launched into serial production in 2015. But in 2017, Russian Defense Minister Shoigu announced that the Premier will be ready only in 2020. That term, however, also wasn’t final and this year it has become clear that the terms are being «shifted to the right» again, this time to 2024.

The voiced reasons for the delay differ each time, but it’s safe to say that they are directly related to the international sanctions against Russia, since it is particularly in the high-tech industries, including electronics, that Russia has the biggest problems with import substitution.

To date, the new MS-21-300 medium-haul narrow-body aircraft, dubbed in Russia «The aircraft of the XXI century,» has trouble getting an international certificate.

Initially, the start of serial production was scheduled for 2017, but then the «adjustments» started: first for 2018, and later — for 2020. At the end of February 2019, the issue was postponed to 2021, and there is still a possibility of further postponement to 2025 due to sanctions against the UAC and Rostech.

Specifically, because of the US sanctions against JSCs Aerocomposite, part of the UAC, and Romashin Technology, part of Rostech, introduced in autumn 2018, the American Hexcel and the Japanese Toray Industries stopped supplying materials for the MS-21 composite «black wing.»

The forced rejection of composite materials with a transition to metal made the whole project meaningless, since in that case, the MS-21 was no longer a competitor to Airbus and Boeing. At the same time, composites from other foreign suppliers significantly differed in quality, while Russia didn’t have the adequate expertise. But in February 2019, the head of the Russian Ministry of Industry and Trade Denis Manturov told reporters about the testing of domestic component prototypes for MS-21 that according to him, «confirmed that the replacement material will not affect the aircraft features.»

There are other difficulties as well. Initially, it was assumed that the share of domestic components for the MS-21 will amount to 38%, but the government has set a goal to increase this number to 97% by 2022, so as not to depend on imported supplies.

But on September 30, 2020, the director of the Radioelectronic Industry Department of the Russian Ministry of Industry and Trade announced that a number of foreign companies supplying ready-made systems for Russian civil aviation had refused to supply and cooperate. The restrictions will primarily concern microelectronics.

«In fact, without announcing the sanctions, they said that they would no longer supply the systems. In other words, they are simply trying to shut down our entire civil aviation construction» said the Department Director.

As for the «civil aviation,» the first USSR long-range radar detection aircraft carrier TU-126 was created on the basis of the civil TU-114. The aircraft that from the beginning was positioned as civilian, is capable of carrying various weapons systems.

Given how Russia uses the occupied Crimean peninsula, the «Crimean sanctions» should not apply exclusively to the Crimean enterprises. Only a comprehensive system of international sanctions, covering a wide range of technologies, equipment and components, would be capable of reducing the Russian military threat and speed up the deoccupation of Crimea.

* * *

The Crimean Library section on the blackseanews.net website has been created with the support of the European Program of the International Renaissance Foundation. The views of the authors do not necessarily reflect the position of the International Renaissance Foundation

More on the topic

- 01.07.2021 The Electronic Catalogue Research by Western Think Tanks on Crimea and the Situation in the Black Sea

- 11.06.2020 The Maritime Expert Platform Association on Urgent Actions to De-Occupy Crimea and Counter the Occupation of the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea. Proposals

- 06.06.2020 The Real Impact of Crimean Sanctions (10-11). The Cost of the Occupation to Russia and What Awaits Crimea and Sevastopol

- 06.06.2020 The Real Impact of Crimean Sanctions (9). The Updated "Crimean Sanctions Package"

- 20.05.2020 The Real Impact of Crimean Sanctions (6-8). The Peculiarities of Economic Processes in Russia and Occupied Crimea under Sanctions

- 18.05.2020 The Real Impact of Crimean Sanctions (5): the Imposition of U.S. Sanctions against Russian Plants over the Production of Warships in Crimea

- 09.05.2020 The Real Impact of Crimean Sanctions (4). Missed Deadlines for the Production of Karakurt Missile Corvettes at the Morye Shipyard in Feodosia

- 07.05.2020 The Impact of Sanctions on Maritime Connections with the Occupied Crimean Peninsula (3)

- 05.05.2020 The Real Impact of Crimean Sanctions (2). The Impact of Sanctions on the Crimean Banking

- 04.05.2020 The Real Impact of Crimean Sanctions (1). The State of the Sanctions Regime as of 1 February 2020

- 03.03.2020 The policy of non-recognition of the attempt to annex the Crimean peninsula

- 13.02.2020 Russia's Economic War Against Ukraine in the Sea of Azov as of February 1, 2020. The Technology of Blocking the Mariupol and Berdiansk Ports